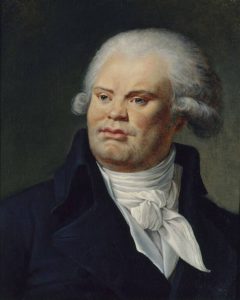

Breaking News: Discover the Chilling Tales Behind Charles-Henri Sanson, the Master Executioner of France!

From the era of the sword to the advent of the guillotine, Charles-Henri Sanson was a figure steeped in the shadows of history, having executed approximately 3,000 individuals over the course of his bloody career. His life intersected with some of the most tumultuous moments in Frances past, marked by a peculiar sense of duty and an unsettling profession that demanded both a technical expertise and an inescapable moral burden.

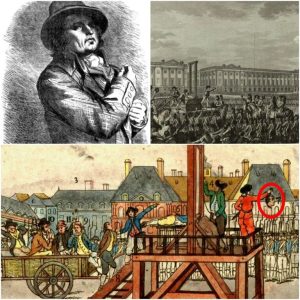

On January 5, 1757, history took a pivotal turn when King Louis XV of France left the grand halls of the Palace of Versailles. As he made his way to his carriage, a strange man suddenly collided with the palace guards, stabbing the king in the chest with a small knife. The assailant was swiftly apprehended, while the bloodied king was ushered back inside, suffering what turned out to be a minor injury. Although the threat to his life had subsided, King Louis quickly shifted his focus from self-preservation to the fate that awaited his would-be assassin, one that would unfold in a gruesome public spectacle.

On March 28, Robert-François Damiens, a religious fanatic turned failed assassin, was led to Place de Grève before the Hôtel de Ville in Paris. There, he faced a brutal, ritualistic torture in front of an exuberant crowd that had gathered to witness the drama. His flesh was torn away using red-hot iron pincers, while the very knife that had sought to take the kings life was melted into his hand with sulfur. In a final, horrific act, the executioner bound each of Damiens limbs to a different horse and set them off in opposing directions. After a torturous two hours, failing to dismember him entirely, the executioner drew a sword and finished the job, subsequently setting Damiens’ still-living torso ablaze, reducing the failed assassin to ashes.

Wikimedia Commons

The execution of Robert-François Damiens was a spectacle that captivated the audience, including the renowned Giacomo Casanova, who happened to be in Paris at the time. Spectators reveled in the macabre display, and for the 17-year-old executioner, Charles-Henri Sanson, it was simply another day at work, albeit one that would forever stain his legacy.

Charles-Henri Sanson and the Harsh Code of Execution

Wikimedia Commons

Born into the lineage of executioners in Paris on February 15, 1739, the Sanson family had served the French monarchy for three generations. At a time when career paths were more often dictated by heredity than personal choice, Charles-Henri was thrust into a brutal legacy. His tenure as Paris executioner began in 1754 when his father, Charles Jean-Baptiste Sanson, was afflicted by a sudden illness, rendering him paralyzed on one side for the rest of his life. With his father unable to fulfill his duties, young Charles-Henri found himself navigating the treacherous waters of a profession steeped in brutality and societal disdain, even though he would not formally take over until his fathers death in 1778.

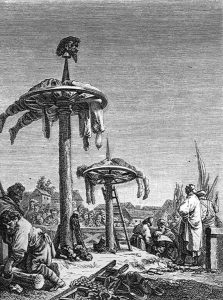

For centuries, the French judicial system upheld a peculiar social hierarchy concerning crime and punishment. Nobles found guilty of capital offenses faced decapitation, typically by sword, due to the cleaner cut it provided compared to an axe. Commoners, on the other hand, experienced hanging, a process requiring significant mathematical precision to ensure an immediate break of the neck. The most heinous criminals suffered the cruel fate of being broken on the wheelspread-eagled upon a cartwheel while their limbs were mercilessly shattered before being mercifully finished off.

Wikimedia Commons

To be an effective executioner, or what was officially termed a “public executioner,” it was necessary for Charles-Henri Sanson to master not just the technical aspects of these gruesome procedures but also their symbolic and theatrical elements. As Monsieur de Paris, he was required to present himself in public garb distinguished by a red cloak. After executions, it was not uncommon for desperate souls to reach out to touch the hand of the executioner in hopes of acquiring his supposed healing powers, especially if his hands were still stained with blood.

Despite the grim dignity that accompanied his position, the populace harbored a deep-seated fear of executioners, often tinged with superstition. While technically of noble status, the Sansons were denied the privilege of collecting their rightful earnings due to the associated stigma. In church, they were often assigned a separate bench and faced the scornful spitting of the congregation as they passed through, a testament to their pariah status in society.

This was the reality into which Charles-Henri Sanson was born, yet it was not the environment in which he would ultimately die, as the winds of revolution began to stir.

Whispers of Revolution and the Rise of the Guillotine

Wikimedia Commons

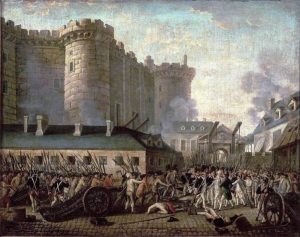

The first indication of an impending shift came in 1788 when Charles-Henri Sanson and his sons, Henri and Gabriel, were called to oversee the execution of Jean Louschart in the village of Versailles. Convicted of clubbing his father to death during a heated argument, Louschart was to be publicly tortured on the wheel near the grand palace. However, the execution was violently disrupted when a group of sympathetic villagers stormed the stage, rescued the prisoner, and set the execution wheel ablaze before the spectacle could be completed.

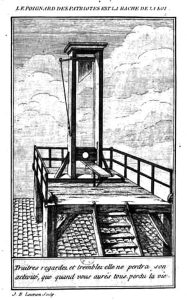

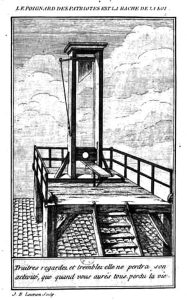

While the Sansons escaped the wrath of the mob, the judicial system they represented did not. As the parliamentary body known as the National Constituent Assembly convened to discuss reforms, the events in Versailles ignited critical conversations about public executions and the role of executioners. In 1789, the government abolished the privileges and biases towards executioners, proposing a uniform method of executiondecapitationfor all, echoing the ideals of Enlightenment thought regarding social equality. Yet, Charles-Henri Sanson, drawing on his extensive experience, recognized the inherent challenges in implementing this new method efficiently.

He knew firsthand that achieving a clean beheading, even with a sword, was an unpredictable task. Deeply haunted by a past experience where he had inadvertently tortured a former friend of his father’sCount Lallyby failing to sever his head in a single blow, Sanson became an early advocate for a new invention proposed by Dr. Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, a machine designed specifically for decapitation. His involvement in its testing and refinement would prove pivotal.

Wikimedia Commons

Sanson, Guillotin, and royal surgeon Dr. Anton Louis collaborated intensively to perfect the mechanics and design of this revolutionary device. Legend has it that Tobias Schmidt, a German harpsichord maker and a friend of Sanson, contributed to the final construction of the guillotine. There are tales suggesting that Dr. Louis, Guillotin, and Sanson even sought the approval of King Louis XVI, who was under house arrest, for the contraption. The king, a known enthusiast of mechanics and lock-making, endorsed the design while suggesting modifications to angle the blade instead of keeping it flat, thus allowing for better weight distribution.

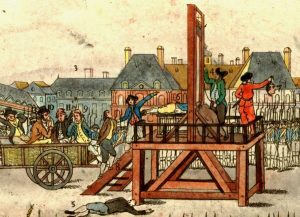

Finally, after months of experiments involving bales of hay, pigs, sheep, and even humans, the guillotine, as it became known, was poised for its inaugural demonstration. On April 25, 1792, the new device claimed its first victim: Nicolas-Jacques Pelletier, a notorious highwayman who was reportedly horrified by the strange mechanism awaiting him.

Wikimedia Commons

Although crowds gathered as usual at the Place de Grève to witness this grim entertainment, they were dissatisfied with the rapidity and efficiency with which the guillotine operated. Discontent quickly turned to fury as they clamored for the return of their beloved wooden gallows, leading to violent clashes with the newly formed National Guard, resulting in the unfortunate deaths of three civilians.

There were indeed elements amiss with the guillotine. Following the execution of Charlotte Corday, the woman who assassinated revolutionary leader Jean-Paul Marat, spectators noted that Cordays severed head appeared to exhibit facial expressions when slapped by one of Sansons assistants. From that moment forth, executioners began to suspect what would later be scientifically confirmed in the 20th century: the guillotine acted so swiftly that the head could potentially remain sentient for several seconds post-decapitation.

Wikimedia Commons

Yet Charles-Henri Sansons concerns regarding the device were rooted in deeper personal ramifications. On August 27, 1792, shortly after the monarchy collapsed, his son Gabriel tragically fell from the gallows while displaying a severed head. Weeks later, haunted by guilt and disturbed by the September Massacreswhere over 1,000 prisoners were executed in fear of their potential support for a counter-revolutionSanson tendered his resignation to the new authorities. However, his resignation was unceremoniously denied.

In January of the following year, both the guillotine and Charles-Henri Sanson stood immortalized by what would become their most notorious act: the execution of King Louis XVI.

The Death of the King

Wikimedia Commons

From the moment the monarchy was abolished and the royal familys failed escape attempt from France, the fate of the dethroned king had been a matter of intense speculation. Despite not being particularly politically inclinedspending his meager free time reading, gardening, and playing the violinCharles-Henri Sanson identified as a monarchist at heart. Louis XVI was the monarch who had officially bestowed his title upon Sanson. Without the kings authority, one might argue, was he truly any better than the assassins he was tasked to eliminate?

According to the memoirs of Charles-Henri Sansons nephew, the night before Louis XVIs execution, scheduled for January 21, 1793, the Sanson family received a threatening message indicating a conspiracy was afoot to save the king. If this tale is to be believed, the executioner arrived at the Place de la Révolution (now known as Place de la Concorde) equipped with swords, daggers, four pistols, a flask of strength, and pockets full of ammunition, prepared to rescue Louis XVI if needed.

Whether or not the plot was indeed real, a rescue party never materialized. Instead, Louis XVI was formally introduced to the public, greeted by Charles-Henri Sanson accompanied by a roll of drums. The charges against the kingaccusations of conspiring against the French peoplewere read aloud as he uttered his last words: You see, your king is willing to die for you. May my blood cement your happiness, only to be interrupted by the sound of beating drums. Sanson then laid the king down upon the guillotines platform and carried out his grim duty.

As the crowd surged, liberated citizens rushed forward to wash themselves in the monarchs blood, even collecting it on their handkerchiefs. Although rumors circulated that Sanson had sold locks of Louis XVIs hair, historical documentation makes such claims seem unlikely. In his diary, he recorded, The sacrifice is accomplished. Yet, the French populace did not appear to share in his satisfaction.

The Reign of Terror

Wikimedia Commons

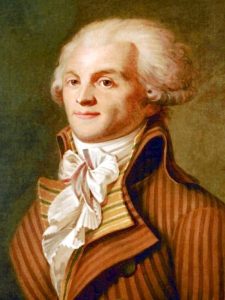

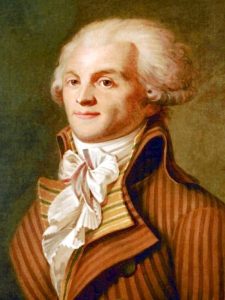

Under the revolutionary government led by Georges Danton and Maximilien Robespierre, paranoia regarding internal enemies led to an increasingly simplified judicial process, resulting in an escalating number of executions in 1793 and 1794. Dubbed The Terror by its instigators, Robespierre insisted it was nothing short of justiceprompt, severe, and unyielding.

However, this meant that Charles-Henri Sanson found himself working harder than ever before. Following the execution of Marie Antoinette, France’s dethroned queen, the number of daily executions surged from three or four to dozensat times reaching more than 60 beheadings in a single day. The stench of blood became so pervasive at Place de la Concorde that even farm animals began to refuse to cross it.

Wikimedia Commons

As the grim realities of the Terror became a routine facet of daily life, the once-infamous Charles-Henri Sanson found himself elevated to a peculiar status. Formerly, people would stop to stare, whispering as he passed. Now, he was affectionately addressed as Charlot! (little Charles or Charlie) on the streets. There were even discussions of officially dubbing him The Avenger of the People, with his green attire becoming a fashion trend among the revolutionaries.

The guillotine itself gained unparalleled popularity as the execution method of choice, rivaled only by the Christian cross. Children began to use toy guillotines to kill mice, and the device appeared on buttons, pins, and necklaces. For a time, even guillotine-shaped earrings became a minor sensation.

Yet beneath the surface, new power struggles were brewing. Danton, the populist leader, and Robespierre, the idealistic demagogue, had always been uneasy allies, bonded by the forces of revolution. Having previously eliminated most of the monarchists and remnants of the moderate Girondins, it was only a matter of time before they would turn against one another. Robespierre struck first.

Wikimedia Commons

Stoking the anti-Danton fervor within the revolutionary government, Robespierre and his accomplices soon orchestrated Danton’s arrest on charges of corruption and conspiracy, largely stemming from alleged financial irregularities and illicit accumulation of wealth on March 30, 1794. It is said that as Danton rode in Sansons carriage toward the scaffold on April 5, he remarked, What annoys me the most is that I will die six weeks before Robespierre. He was only slightly off with his timing.

The Beginning of the End

Wikimedia Commons

Robespierres last hurrah, the Festival of the Supreme Being, occurred that June. After banning Catholicism throughout France, he established a national deist religion, appointing himself the high priest. Charles-Henri Sanson found himself at the forefront of this spectacle, accompanying his son Henri on either side of the guillotine, which was referred to as The Holy Guillotine, atop a blue velvet parade cart adorned with white lilies on the Champ de Mars.

Ultimately, after nearly four decadesthe longest tenure of any executionerCharles-Henri Sansons experiences became too much for him to bear. What I feel is not pity; it must be a nervous imbalance, he would write in his diary. Perhaps I am being punished by the Almighty for my cowardly compliance with this mocking justice. For some time, I have been tormented by terrible visions… I cant convince myself of the reality of what is occurring.

He began to suffer from persistent fevers and would often see bloodstains on the tablecloth during dinner. Soon after, he collapsed into a delirious state and fell into a dark mood from which he would never recover. His son took over his position before being arrested on dubious charges, but before Henri Sanson could meet the same fate, Robespierre himself would ultimately face his own end.

A victim of the same swift justice that he had inspired, Robespierre was accused of believing himself to be the messiah and was arrested. He attempted suicide with a pistol but failed, instead fracturing his jaw and losing his ability to speak in his own defense.

Charles-Henri Sanson recovered enough to witness the final execution. Following Robespierre’s execution on July 28, noted for the potentially disdainful way the executioner removed his blindfold, leaving the victim screaming as the blade fell, Sanson remained only long enough for his son to take his place.

The Last Laugh?

Little is known of Charles-Henri Sansons retirement. He settled in the countryside, residing in the same house as his father, tending to the garden and helping to raise his grandson, Henri-Clément, far removed from the morbid celebrity that defined Sansons reputation.

With a touch of irony, Sanson was denied a pension due to a legal technicality, as he had not officially inherited his title until after over 20 years of service. He passed away in 1806, having aged prematurely, some say due to the toll of personally executing nearly 3,000 people.

However, there exists one last story, albeit unconfirmed. It is said that early in the reign of Napoleon I, the retired executioner and the emperor crossed paths near Place de la Concorde, the same site where Sanson had executed the last king a decade prior. Recognizing Charles-Henri Sanson, Napoleon reputedly asked if he would do the same to him if necessary. Disturbed by the affirmative response, it is said Napoleon queried how he could sleep at night.

To which Sanson allegedly replied, If kings, emperors, and dictators can sleep soundly, why shouldnt an executioner be able to do the same?”

Leave a Reply